AI might not solve our problems, but understanding where it came from could help us solve climate change.

1. Acceleration

Stepping back, AI, which was 10 years out three years ago, is now everywhere. How did that happen? In a nutshell, AI was being developed in fragments: one building might have people working on Image classification to pick photos with fire hydrants in them; one might test natural language processing which tries to map words and their meaning to hold conversations; another might train DNA analysis models; etcetera.

A few people noticed this fragmentation, along with a common denominator: All of the models handle what could otherwise be understood as language.

Images? They're just numeric color values, which are stored as text.

DNA? Literally four letter patterns. Stored as text.

Music? Give me a tone and a volume value. You have MIDI, also stored as text.

Given a large enough collection of labeled images, books, music, and science, one giant model would be capable of tying different languages together.

Think of datasets like cork boards with pins holding up all kinds of things, AI is like a detective tying strings between the pins. Bigger cork board + more strings = bigger picture.

This is the story of OpenAI—which alone changed the course of AI; I think a similar methodology can change the course of climate change, while also globally improving social mobility, economic stability, and public health.

I believe the exact same methodology can apply to people, and as an example, I've done it.

2. Academia

In academia, fields are generally monolithic, with double-majoring or combined degree programs being the closest undergrad students can get to interdisciplinary study. Even in these programs, the focus is still on two separate fields, not a union of them.

The way you begin to solve this issue is by realizing specific fields encompass many others while adding measurable outcomes, I refer to these as upstream or downstream studies, where downstream fields can see what other fields are affecting their outcomes, but people upstream might have no idea about these connections.

At graduation students are usually specialized and connected to others in their specialty, but they're ill-equipped to handle complex issues. Base understanding in multiple backgrounds is paramount to a big picture view, but access to unrelated fields is financially and methodologically gate-kept; electives are expensive and limited, so students prioritize studying things they're interested in rather than venturing out.

Our system breaks problems down to understand specific aspects of them, but because they are so deeply inter-connected it's hard to know where to start, how far up or downstream you are, with one major exception: public health.

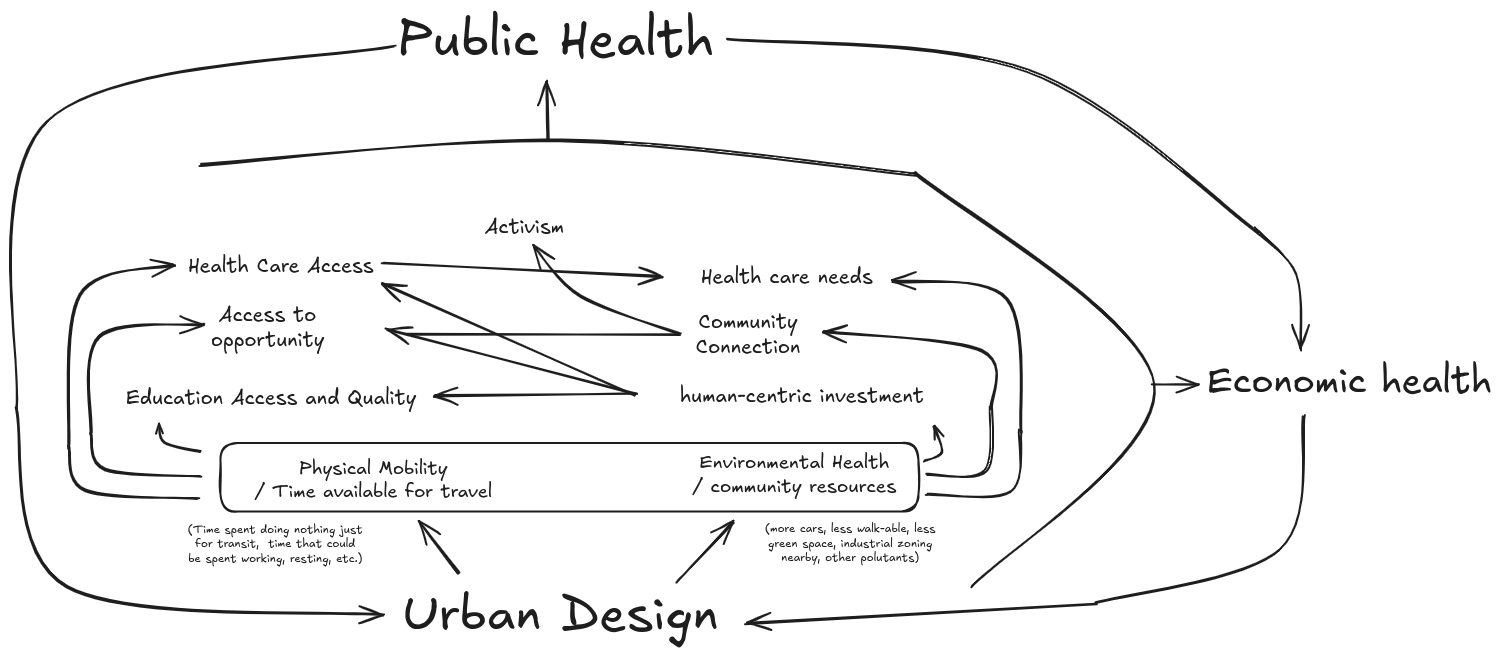

One of the earliest things you learn in public health is the SDOH model, or social determinants of health, that is, socially constructed systems that determine health outcomes, and when you begin to see that almost all of them stem from one area, foresight becomes 20/20.

That one area is urban design.

3. Places

The way we navigate and interact with each other has shifted dramatically over the last century, from splitting and spreading cities apart to make room for cars, to moving communications online, but across every context where tech is fulfilling a need I oftentimes feel that it is only band-aiding a bigger problem, with many stemming from poor urban planning.

The biggest threat to our future is Climate Change, and across almost most discussions and lectures I've found the focus has been on individuals and companies, for example: how can companies reduce their emissions? How can consumers reduce their carbon footprint? How can we help other countries avoid growing their footprint? I think this approach while well intended is misguided and will lead to our demise.

The reason we emit so much is not because emissions are inevitable like oil companies would like us to think—we had dense, well designed cities with electric trains as far back as 1895, before oil really entered the picture.

Our transition to car-centric infrastructure has not only hindered our economy by separating people from businesses, polluted our environment with particulate matter from exhaust, tires breaking down, and nose, but also makes us more dependent on consumption because we consume larger amounts of resources fewer and further between.

Instead of filling up a tote bag of ingredients from a local grocery shop next door, we drive an average of 3.8 miles and load up for the next week, often in non-reusable packaging because of the increased difficulty of transporting things in an environmentally friendly way, and then end up throwing out 2.1 pounds of edible food per week.

The increased demand for consumables means more time is spent running errands and more resources for sustaining your life, it not only becomes more expensive to live, but the quality and quantity of life you experience also goes down.

Even systemic racial violence is embodied in car-centric design, because the construction of freeways and red-lining paved the way for cars to become dominant, and to this day have long lasting impacts on economic mobility, social and public health acting, with freeways acting as literal dividers through communities.

4. Urban Economic Engineering: Our future can be brighter than ever if we reach for it

Put simply, UEE rolls public health, economics, and urban-design into one field of study with public health being the guiding back-bone, economics being a secondary measure of how many people are included and engaging with other's, and urban-design being the control variable that creates the other two.

Practically, many US cities and infrastructure will be in need of re-works within the next decade, while a lot of discussion around climate change is from a doom and gloom perspective of what we'll lose (Oil, says the oil companies) I believe it's a once in a lifetime opportunity to create the urban environments we dream of, we can use our country's vast military industrial infrastructure to rapidly iterate on infrastructure and deploy large scale rapid-transit systems across the country, we can rebuild parking lots into affordable-housing with solar living roofs and mixed-use pavilions with parks and music, and scale back our sprawl to restore natural environments giving ecosystems a chance to recover.

Building new mixed-use environments also improves community cohesion and creates opportunity; there's many more benefits to it. UEE isn't the end solution in itself, but it's a comprehension tool to move in the right direction, much like how OpenAI put two and two together to handle more complex data, UEE is the idea that to understand economics, we need to do so not from the perspective of business, but as emergent systems of individuals interacting with others on a local, personal level at a large scale, and that we can use this to direct policy.

Simply put, we can have our cake, the economy, and eat it too, solve climate change and substantially reduce inequality.

When the majority does well in small environments on a large scale, the economy grows with them horizontally, allowing for stable, sustainable integration. It might not look like the vertical systems we have now, but it could be anything and everything we dream of.

Back to articles